|

Background Plain Weave |

Marcy Petrini

March, 2025

I have just finished teaching a MAFA zoom class on tied unit weaves to a wonderful group of weavers, so I have been thinking some more about tabbies.

In the February blog, we discussed how tabby can refer to the ground cloth of a supplementary weft structure. As I mentioned, on four shafts, the tabby treadling for overshot is 1 & 3 vs. 2 & 4, odd vs. even; for summer and winter, a tied unit weave, the tabby treadling is 1 & 2 vs. 3 & 4, or tie shafts vs. all pattern shafts. Thus, on eight shafts the treadling for the background tabby of summer and winter becomes: 1 & 2 vs. 3 & 4 & 5 & 6 & 7 & 8.

I kept that rule in mind as I studied other tied unit weaves. The rule applies to some, for example it applies to the single, three unpaired ties, 1:1 ratio, called “Half Satin”, shown below (all drawdowns are sinking shed).

The tied unit weave structure called “Tied Latvian” (double two paired ties with 1:2 ratio), however, uses the odd vs. even treadling as shown below:

There are many variations for treadling the background among tied unit weaves. One example is “3:1 Beiderwand“ which is a double, two unpaired ties structure, with a 1:3 ratio and the pattern shafts organized in reverse pointed twill order with the ties. As a result of this interesting arrangement, the tabby ground is formed by treadling the pattern ties plus the odd pattern shafts vs. the even pattern shafts as shown below.

One day I was ready to weave “2:1 Beiderwand”, a double, two unpaired ties with a 1:2 ratio. I always weave a background tabby header to start, to double check threading and sleying. This tabby ground, however, was not weaving correctly. After checking my threading and tie-up several times, I went back to the drawdown: and there it was! A true tabby cannot be woven across the fabric as we can see from the drawdown below.

Plain weave is formed underneath the blocks on both sides, but not across the fabric.

I should have used the sure way to determine whether any threading will produce plain weave across the fabric. Set up two lines, treadle 1 and treadle 2. Alternate the threads in the threading in the two treadles. For example, block A of “2:1 Beiderwand” from the drawdown above is: 1, 3, 4, 2, 3, 4. We alternate these six threads:

Treadle 1: 1, 4, 3

Treadle 2: 3, 2, 4

We don’t have to go past the first block to realize that weaving a tabby across the fabric is impossible as shafts 3 and 4 appear in both treadles. Those two shafts will stay up or down with every tabby pick preventing interlacement.

I have used this method for complex twills, for example. I was just lulled into a false sense of security that all tied unit weaves were following the rules.

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Tabby |

Marcy Petrini

February, 2025

Earlier this month, I gave a presentation to the Westfield Weavers Guild on plain weave, setts, different size threads, and color interactions.

At the end of the talk, my friend Catherine Marchant asked a question about tabby, which has gotten me thinking about the different ways we use the word.

The fabric determines the structure, and a tabby cloth is a balanced plain weave: the same number of warp ends per inch and picks per inch, as shown in the sample below. For example, the sett may be 12 epi and the weft is 12 picks per inch.

What about 13 picks per inch, or 11? Is that still a tabby cloth? Let’s not get too technical, but we can all agree that the fabric below is not a tabby, it’s a weft dominant plain weave.

The treadling steps to achieve that plain weave, whether is tabby or plain weave, depend on the structure, but we tend to call tabbies the treadles which are attached to the shafts that will produce plain weave when used.

For example, if I am weaving a compounded fabric with a supplementary weft, for example overshot or summer and winter, I may say that I always put my tabbies on the right side of the treadles. However, these treadles will be different for these two structures.

For overshot, my tabby treadles are:

|

|

4 |

|

3 |

|

|

|

2 |

|

1 |

|

For summer and winter, my tabby treadles are:

|

|

4 |

|

|

3 |

|

2 |

|

|

1 |

|

As long as we know the structure, we know what we mean by tabbies, and we can attach the shafts to whatever treadles we find convenient to weave.

However, do these tabbies always produce a true tabby?

When I sample structures with a supplementary weft, I like to use 10/2 cotton for warp and ground weft. My sett for the warp, however, is not the 24 epi that I would use to make a tabby in a simple cloth (simple by Emory’s definition, one warp, one weft). I use 18 epi to allow room for the supplementary weft.

Within the compounded fabric, that ground cloth is, in fact, a tabby: a sett of 18 and 18 picks per inch for the ground weft, as shown in the summer and winter sample below.

A supplementary weft fabric means that the supplementary weft is not needed for the integrity of the cloth. If I were to cut out the supplementary weft that produces my motifs, I would be left with a tabby: 18 epi and 18 ppi – a rather loose fabric, but balanced.

Some weavers, however, prefer to sett the warp as they do for a true tabby. Thus for the 10/2 cotton, they would sett it at 24 epi. To give room to the supplementary weft, then they use a smaller ground weft, for example 20/2 cotton.

Now we have a ground cloth of 10/2 cotton sett at 24 epi and a ground weft of 20/2 cotton which presumably weaves at 24 ppi.

Is that tabby? It’s definitely plain weave!

We can ask the same question of rectangular float weaves (Emory classification) which are derived from plain weave: huck, huck lace, Bronson lace, spot Bronson, etc. For example, huck lace can have areas of plain weave as shown in the fabric below.

On four shafts, the tabbies for huck lace are those of plain weave 1 & 3 vs. 2 & 4, not surprisingly, since the structures is based on plain weave.

But is the plain weave area tabby? In the fabric above, it doesn’t look it. When I weave lacey weaves, I chose the warp sett depending on the effect I want: balancing lacey areas and plain weave, I may use the tabby sett; if I have lots of lacey areas and I am afraid that the fabric will be too sleazy, I may increase the sett; conversely, if I use huck which has lots of plain weave areas, I may decrease the sett to increase the drape for the lacey fabric.

So, are those plain weave areas tabby? They are plain weave!

In weaving, we always have grey areas…..it’s ok, just as long as we know what we are weaving, and we like the final result!

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Introducing the Block-aid©! |

Marcy Petrini

December, 2024

|

BTW - Earlier this month |

A free on-line resource to describe blocks!

(https://www.marcypetrini.com/marcy-s-blogs/385_the-block-aid)

Why Block-Aid©? Read on…

Soon after I started weaving, I discovered blocks: an overshot table runner, huck lace shawl, summer and winter pillow. I just wove for fun and to learn about the different structures, but not really paying attention to how they are similar or differ.

When I started to weave on more than four shafts, I began to think about block differences. We can just repeat blocks of summer and winter by mimicking the threading of the first block as shown below: each block is always shaft 1, pattern shaft, shaft 2, pattern shaft. As we weave each block, the remainders of the blocks weave a combination of warp with pattern and ground wefts. (The drawdown is sinking shed to show the blocks more easily).

This method doesn’t work for overshot. We can mimic the block threading so that each new block is formed by dropping the first shaft and adding the next, as shown in the drawdown below. However, when we treadle the blocks the same way we do on four shafts, the floats between woven blocks are too long. For example, if we weave block A, there will be half tones in blocks B and H, but the weft will float over the plain weave ground from blocks C through G. (The drawdown is rising shed to show the long weft float).

About six or seven years ago, I decided I really needed to concentrate on the differences among blocks. By then I had become familiar with Emery’s weaving classification, so I first chose rectangular float weaves, as she calls them. I think of these structures as one shuttle weaves that form blocks that are an integral part of the cloth.

The other group of weaves I wanted to learn more about was tied unit weaves. I first learnt their nomenclature from a workshop by Donna Sullivan on summer and winter. It was time to get back to those structures. I submitted and got accepted for both topics as seminars at Convergence® 2020 which was postponed till 2022. It just gave me more time to weave samples!

There are, of course, other blocks. As I was thinking of systematically approaching the problem, I decided to submit a seminar for Convergence® 2024 called “Not All Blocks Are Created Equal.” From the drawdowns above, we already can see that we can’t simply substitute the “rules” of one structure to another.

The more I learned – and still learn – about blocks, the more I find new ones. I was getting organized for my MAFA on-line class just earlier this month, when I realized that putting these blocks in a single monograph was a losing proposition: it would be incomplete the minute I sent it off to the class participants!

That’s when I came up with the idea of Block-Aid©. Along the same line as the Pictionary©, each block has its own downloadable pdf file, with photos of fabric, drawdown, descriptions of the blocks, going from four to more shafts when applicable, and other details specific to the block. Unlike the Pictionary©, Block-Aid© is not one page per block!

On the website right now with the link above are final drafts of the various blocks. The information is fine, the format may change. We will announce as blocks are finalized and when new ones are added. I already have a long list of blocks to add. More samples are needed!

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

Double Summer and Winter |

Marcy Petrini

January, 2025

Between holiday gatherings and anniversary celebrations (our 50th!), we finally finished the revision of the first Block-Aid© entry: Double Summer and Winter.

The layout has been changed for (hopefully) easier reading and obtaining information. The twelve pages are in a PDF which can be downloaded.

WIFs of all the drawdowns can be downloaded in one of two ways:

individually by clicking on the specific drawdown within the PDF,

or

all zipped together as an alternate entry in the table of contents.

Try it!

Here is the link for the Block-Aid© table of contents. Double Summer and Winter is in the Common Name alphabetical listing,

with the zipped WIF files available separately. (All other entries are still drafts.)

Alternatively, you can click on this link to go directly to the Double Summer and Winter PDF.

This and more tied unit weaves will be discussed at the upcoming MAFA class I will be teaching. Click here to register - only one spot left!

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

|

More Blocks! |

Marcy Petrini

November, 2024

Just a few days away!

Because of this seminar, I have been thinking a lot about blocks…. More to come in December.

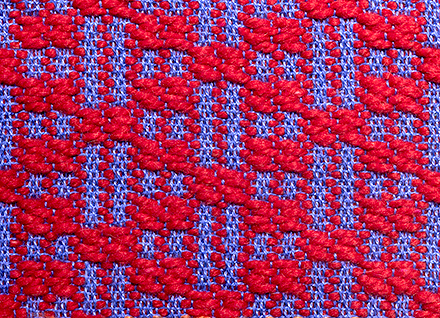

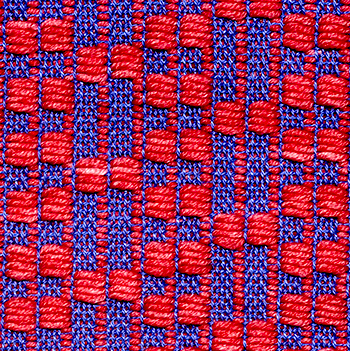

Meanwhile, here are two of my favorite blocks.

Can you believe that they were woven on the same threading? Do you know what they are?

Happy Weaving!

Marcy

Page 1 of 28