What is a Block?

Marcy Petrini

June, 2018

Block is a term that describes any structure forming floats organized in squares or rectangles. A color gamp has blocks of color, a twill gamp has blocks of twills woven with different treadling; and, given enough shafts, any structure can be organized in blocks.

Traditionally, the term has been used for structure that form organized floats inherently. Basket weave and the group weaves – huck and huck lace, Spot Bronson and lace, Swedish lace and M’s & O’s – form blocks as an integral part of the cloth. The three weaves below – overshot, crackle and summer & winter – form blocks using an additional pattern weft; their similarities make them confusing, so here is a comparison of the three.

Click here for the full-sized table (a PDF will open a new window)

Overshot, tromp as writ, also called star fashion:

Crackle traditional, each block a different color:

Summer & winter, treadled as singles:

Each one of these structures offers many more options, but I hope these comparisons help you differentiate between them.

Please email comments and questions to

Name Draft Symmetry

Marcy Petrini

May, 2018

In the previous two blogs we discussed the schemes and the rules for designing a name draft using overshot, and then how the draft could be adjusted with incidental threads to make it symmetrical. Our other option for making the draft symmetrical is to flip it, much as we do to produce a pointed twill, or in our case a reverse pointed twill, as shown below:

|

|

And we combine it, remembering to eliminate one of the “1”s in the middle:

Similarly, we can flip our overshot blocks. Here is our original threading:

And here is the symmetrical draft pivoted around block A (1, 2) in the middle, shown in the lighter blue, reducing it to 5 threads:

The reduction also occurs when we thread more than one repeat, as shown below; the light blue is once again the pivots for the two repeats; the dark pink is the combined block A for the end of the first repeat and the start of the second; the total number of threads is also reduced.

Below is the tromp-as-writ drawdown, or star fashion:

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

And here is the rose fashion:

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

Remember that in these drafts, what looks like long warp floats are, in fact, tabby areas as the tabby weft is not shown to emphasize the design.

All the drawdowns are derived for a sinking shed loom. Note for example that, in the above draft, all of the threads woven by the first block, D, shafts 1 and 4, are covered: those threads are lowered and the supplementary weft covers them.

While I prefer using numbers for clarity, traditionally sinking shed tie-ups are shown with “X” and rising shed tie-ups with an “O” (think “balloons rise”). To convert a sinking shed tie-up to a rising shed one, we lower the opposite shafts since, for example, when shafts 1 & 2 are lowered in a sinking shed loom, 3 & 4 remain up; in a jack loom, we can obtain the same effect by raising 3 & 4 thus leaving 1 & 2 lowered. Here is how to convert:

| X | X | X | |||

| X | X | X | |||

| X | X | X | |||

| X | X | X | |||

| Counterbalance Loom (Sinking Shed) |

|||||

| O | O | O | |||

| O | O | O | |||

| O | O | O | |||

| O | O | O | |||

| Jack Loom (Rising Shed) |

|||||

I haven’t woven this particular draft, but I have done a name draft of my name a while back, so there are lots of possibilities. Here is the fabric from a previous name draft.

This is the last blog on name drafting, so it’s really your turn! Try your name, or a saying; try different schemes if the first one doesn’t give you a pattern that you like; use various incidental threads where needed, so that a pleasing design results; leave asymmetrical or try strategies to make the threading symmetrical; treadle star or rose fashion – or any of the other possibilities used with overshot.

Please email comments and questions to

Name Draft: An Example

Marcy Petrini

April, 2018

In the previous blog we discussed the schemes and the rules for designing a name draft, using overshot. The information may be made simpler by using an example. I used the first scheme (A = 1; B = 2; C = 3; D = 4; E = 1, etc.) on my name:

| M | A | R | C | Y | P | E | T | R | I | N | I |

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

It is easier to see it as a threading

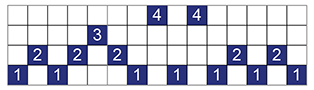

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

We can mark the trouble spots, where two odd threads or two even threads occur next to each other.

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| ⇑ | ⇑ | ⇑ | |||||||||

Next we need to make adjustments; here is a possibility:

| 4 | 4 | ||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||

|

⇑ 2 |

⇑ 2 |

⇑ 1 |

|||||||||

This is the resulting threading:

| 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||

| 3 | ||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

I prefer overshot patterns that are symmetrical, so I can do one of two things: 1) I can choose the 1, 4, 1, 4, 1 block (block D) to be my middle and adjust the threading on either side to make them mirror images of each other by adding 3, 2 on the right side of the middle. Or, 2) I can pick the end of the threading and make that the middle point and reverse it.

Let’s try the first option, adjusting the threading on each side of the middle to make the motif symmetrical:

This is the resulting threading:

| 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||

| 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

We repeat the threading at least once to see what happens at the junction, here we combine the beginning and ending block, avoiding a float too long:

| 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

The tie-up for overshot is generally for a sinking shed loom since we want the threads in a block to be lowered so they can be covered with weft. We will follow this convention; for a rising shed loom, tie the opposite shafts: for example, for shafts 1 & 2 sinking, raise 3 & 4 instead.

To treadle, we “tromp-as-writ” (star fashion), that is, we weave each block as we encounter it: shafts 1 & 2 are block A; 2 & 3 block B, etc., generally using one shot less than the number of threads in the block since one thread is shared between blocks. For example, the first block is 1, 2, 1, 2, so we use three shots. This means that the turning block is treadled with four shots – and yes, that is correct, per Peter Mitchell and Barbara Miller, the overshot gurus.

Below is the drawdown; what may appear as long warp floats really aren’t, they are plain weave areas because in weaving we use a tabby weft, which is not shown in the drawdown in order to emphasize the design.

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

We tend to think of overshot blocks as woven to square, and in the drawdown they appear rectangular, not square. However, the loftier yarn of the supplementary weft and the tabby in between makes the squares the appropriate proportions.

We could add borders, but this is such a small design that I don’t think borders would add much.

Another common way to treadle overshot is rose fashion. In this case, we transpose the treadling as follows:

| To weave block | We Treadle |

| A (1, 2) | 1 & 4 (block D) |

| B (2, 3) | 3 & 4 (block C) |

| C (3, 4) | 2 & 3 (block B) |

| D (4, 1) | 1 & 2 (block A) |

Here is the drawdown. Whether one treadling method is preferred over the other depends on the threading and personal aesthetics.

Click here for the full-sized draft (a PDF will open a new window)

Try your name or a saying! Next time we will explore the other way to make a symmetrical design, using the mirror image.

Please email comments and questions to

Name Draft

Marcy Petrini

March, 2018

When it was announced that the theme of the Chimneyville Weavers and Spinners Guild’s 2018 exhibit was going to be “Here Comes the Sun”, I knew that I should try a name draft. Last year we went to Kentucky to see the total eclipse in August; just as the sun returned, someone in the field where we were parked to watch it started the music blasting – Here Comes the Sun! Perfect.

Shortly after that trip I wove a piece inspired by the eclipse, but the name draft seemed like a must-do. Convergence® writing and weaving samples has put the project on the back burner (the exhibit won’t be till the fall), but I encouraged some guild members to try name drafting with the title, I thought it would be fun to see how many variation we would get.

What is a name draft? It’s a way to design, traditionally using overshot, probably because we have four blocks, more than with other weaves on four shafts. In the way of review, overshot is a supplementary weft weaving structure based on a straight twill. On four shafts, here are the four blocks:

| 4 | 4 | |||||||||

| 3 | 3 | |||||||||

| 2 | 2 | |||||||||

| 1 | 1 | |||||||||

| Block A | Block B | Block C | Block D | |||||||

The threading of each block is usually at least two repeats (for example, A is 1, 2, 1, 2), but it can be more depending on the desired length of the “overshot” weft that covers the block.

Traditionally, the warp and ground weft are of the same size and color, generally neutral, and produce tabby, a balanced 50/50 plain weave by treadling 1 & 3 vs. 2 & 4.

To weave a block, we cover it with the pattern weft, which is two to three times thicker than the ground yarn and loftier. Thus, to weave block A, in a sinking shed loom we would lower shafts 1 and 2; in a rising shed loom, we would raise shafts 3 & 4, thereby leaving shafts 1 and 2 to be covered.

Here is a sample of overshot, the four blocks threaded A, B, C, D, C, B, A. The overshot areas are in dark blue, the tabby areas in white, and the half-tone areas, so called, as can be seen below, because there are both blue and white threads mixed together.

There are many, many overshot patterns available, but it is fun to design our own and name draft is an easy way to do it.

To design a name draft, we first pick a scheme by assigning a shaft to each letter. The scheme per se doesn’t matter, just as long as we are consistent. Here are two examples:

| Shaft 1 = | A | E | I | M | Q | U | Y |

| Shaft 2 = | B | F | J | N | R | V | Z |

| Shaft 3 = | C | G | K | O | S | W | |

| Shaft 4 = | D | H | L | P | T | X |

| Shaft 1 = | A | B | C | D | E | F | G |

| Shaft 2 = | H | I | J | K | L | M | N |

| Shaft 3 = | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U |

| Shaft 4 = | V | W | X | Y | Z |

You could also add numbers and punctuations. And because the number of letters in the alphabet and the number of shafts don’t come out even (26 is not divisible by 4), some like to double up, p and q, together for example, y and z, etc.

Next, we perform the following steps:

• Choose a name or a saying and convert it into threads on the four shafts using the chosen scheme.

• Adjust the threading so that the tabby (1 & 3 vs. 2 & 4) is maintained; that is, an odd shaft must be next to an even shaft; thus, for example, if a 1 is next to another 1 or a 3, we can either eliminate one thread, or add a thread; if we wanted to add, in this case we would choose an even thread, either 2 or 4. Throughout the draft we can use either addition or subtraction, whatever works to make the design pleasing.

• Overshot patterns are generally symmetrical, but they don’t have to be; if your draft doesn’t produce a symmetrical design, and you prefer one, either adjust the draft with incidental threads to make it symmetrical or reverse it to obtain its mirror image.

• If you are planning a finished product, for example, a table runner, add borders if it enhances the design; generally not needed if weaving yardage.

• Treadle tromp as writ (star fashion) or any of the other traditional overshot possibilities.

Are you ready to try one? Try your name, a common way to get started.

Next month – and that’s only two days away! – I will write up an example, using my name. “Here Comes the Sun” will have to be later, after Convergence®!

Please email comments and questions to

Stripes and Gene Davis

Marcy Petrini

February, 2018

In the last blog we talked about warp stripes, but we can add weft stripes, too. The disadvantage is that the weft has to be changed often and there are those pesky tails to deal with. If the cloth is to be used in a garment where the edges don’t show, we can just leave them. Scottish tartans are woven that way if they will be made into kilts or other garments; the fabric is usually wool which is slightly fulled, locking in the ends anyway. The thinner the weft, the less likely is the build-up of extra tails at the edge. We can also use a technique tapestry: tapering the tail by un-plying and making each ply a slightly different length before tucking in the shed.

The advantage of weft stripes is that, if we don’t like a fabric, we can add a bit of pizazz with weft stripes. Of course weft stripes can be planned. Acadian textiles use colored cottons to their best advantages in weaving the weft stripes.

And horizontal wefts are needed to make plaids; this warp striped fabric

Can become this plaid:

When planning stripes, the conventional wisdom is to use contrasting colors – whether in hue, or value or saturation, or some combination of those – and to use the Fibonacci series for pleasing proportions. Originally described by the Italian mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci, it is a sequence where each digit is obtained by adding the previous two, after starting with 1 and 2:

1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, etc.

These ratios have been used since antiquity, are found in nature and they are all around us in everyday objects, for example, our 3 by 5 cards. In our weaving, we can use them in dimensions, for example in inches, or in the number of threads; they don’t have to be used in order, and they can be in ratios; for example, we could double 2 and 5 and make stripes of 4 and 10 threads.

I used these principles for years. Then one day I walked into the Corcoran Gallery of Art (now closed) and there in the rotunda was an incredible painting of stripes, “The Magic Circle”; it was Gene Davis’s work, which I didn’t know at the time. The more I looked, the more I became fascinated. Those stripes didn’t follow any rules for proportions or color, and yet they were so captivating.

Once in my consciousness, I kept on finding more of his work; in 2016 we visited the Milwaukee Art Museum during Convergence and there it is was – his work is unmistakable.

I became curious: what principles does he use? What makes his work so compelling to me?

I bought the annotated catalog, “A Memorial Exhibition 1987” which included many of his paintings as well as essays by various art critics. Gene Davis, who died in 1985, is considered the most prominent member of the Washington Color School; while his art work is varied, he is best known for his color stripes, often in paintings, but also with lights, and other media. I studied his work and spent a lot of time analyzing those stripes. Finally, in order to understand it better, I decided that I needed to make a hanging based on his “Hot Beat”, shown below on the loom

I am not sure that the warp did much for my understanding, but reading about an interview with him gave me the answer; Gene Davis basically said that he applied all of the art rules and then sought to break them!

So, there you have it! Maybe it is best to spend time training our eye and trusting it, so that we can have a feeling for what our stripes should be – Fibonacci or not.

Please email comments and questions to

A big thank-you to Bambi Moise who pointed out the error in the Fibonacci series as originally posted. It should start with two "1's". It is now correct.